An Iowa native, Alyssa Andrews grew up on a diet of microwave corn dogs, Kraft Mac & Cheese, and other staples of the Midwestern middle-class. Her mouth watered at the thought of a pulled pork sandwich, and she dreamed about the next time she could get her hands on a six-piece McDonald’s chicken nugget. However, when she turned 17, Andrews began searching for the hidden consequences of these staples. While she found an ethical problem with eating meat, she also found ties between meat and Iowa’s most popular crop, corn.

When Andrews learned about modern meat production five years ago, she went vegan overnight and never looked back. In terms of reconstructing the Midwestern diet, Andrews is not alone. A 2019 Harris Poll conducted on behalf of the Vegetarian Resource Group revealed that 16% of Midwesterners sometimes or always eat vegan meals.

“Meat is supposed to cost a lot more,” Andrews said. “The government definitely subsidizes [feed]. It’s tough, and you don’t want to put farmers out of business. But in an ideal world, farmers would be able to switch over to more human food. Especially since big-time agricultural production is pretty bad for the eco-system.”

Miles and miles of golden stalks grace the open fields of America’s Corn State, which produces nearly 13 million acres of subsidized corn each year, according to Iowa Corn Growers Association. These fields of gold are viewed as the economic foundation of Iowa, providing jobs and ethanol for the state. However, Iowa vegans, researchers and farmers have begun uncovering this plant’s harmful effects on their environment.

According to the Global Change Data Lab, meat production has more than tripled in the past 50 years, and it has gotten cheaper. In a meta-analysis published in Science, researchers Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek found that livestock and fisheries accounted for 31% of food greenhouse gas emissions without considering land use. Poore and Nemecek also determined that land used for livestock contributed about 16% of additional food greenhouse gas emissions. According to NASA, these greenhouse gases trap in heat and warm the earth, causing adverse weather effects such as Iowa’s derecho.

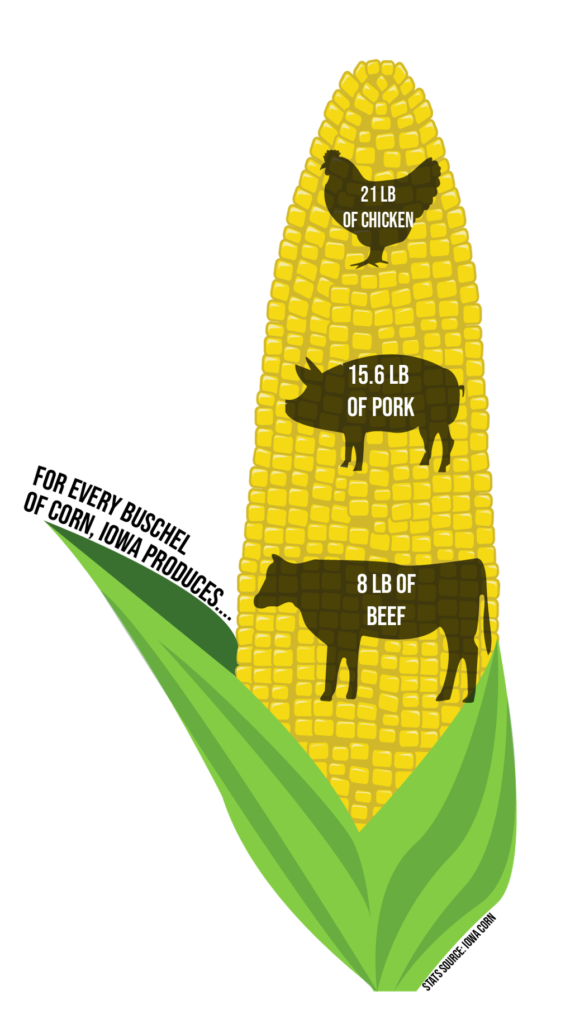

Sylvia Secchi, Ph.D., University of Iowa associate professor of Geographical and Sustainability Studies, said the overproduction that has caused these greenhouse gas emissions is all thanks to corn. According to Secchi, about 50 percent of the corn Iowa produces becomes ethanol while the rest feeds the cows, pigs and other livestock.

“We’ve made those cows eat more corn, so we can produce more corn,” Secchi said. “It’s just with the policies we have right now the only thing we subsidize farmers for is corn and beans. Because the price of corn and beans is lower, it is cheaper to raise animals and the price we pay at the store is lower than it should be.”

Secchi said that corn subsidies caused Iowa to become economically dependent on the meat industry. Since corn feed is so cheap, both the consumer and the producer pay less for meat production. However, Secchi said the environment is paying the price for this cheap meat.

“The real cost to society of eating meat these days is not really what we pay at the store,” Secchi said. “The pollution costs, the air quality costs and water quality costs are not incorporated in the price of meat.”

While Secchi believes the corn and meat industries are harming the environment, an Iowa farmer’s son, Lane Brown, believes Iowans should look to other polluters.

“People think cows are [environmentally] dangerous,” Brown said. “Basically all they do is fart. If you look at it, cars and factories make cattle look like they’re nothing.”

Lane Brown grew up on his family farm which is located just outside Lenox, a small town in southwestern Iowa. Since he can remember, he has been feeding and raising calves. Brown’s family feeds their calves a corn-soybean byproduct, and they rely on Iowa’s corn production to feed their 200 calves. Once the calves are old enough, the Browns sell them to feedlots. Brown said he would prefer his family raise their calves and sell their meat directly to consumers like Secchi recommends, but it is not economically feasible.

“Ideally, the best way would be to raise the calves from start to finish,” Brown said. “But if you’re trying to fatten up a calf to get it to the weight where you can butcher it, it takes about a year and a half. And that first year and a half before you can make that full cycle, you’re going to have to pour an unbelievable amount of money [into it].”

While Brown’s family depends on the meat industry for income, he believes people should eat beef in moderation, along with other sources of protein.

“Personally, I don’t really care if someone eats [meat] or not,” Brown said. “People need to have a wide variety of a diet. I get that some people look at it and think ‘oh I can’t believe people can eat a calf or something.’”

Brown does not see the vegan or plant-based community in Iowa as a threat to his family’s financial wellbeing. However, he could see more people shifting toward plant-based diets.

“Right now they’re trying to grow burgers in factories and stuff, and I do feel like someday people are going to want to switch to that,” Brown said.

In agreement with Brown, Secchi does not advocate for dissolving the livestock industry.

“I think that vegan people have maybe a more extreme approach than most of us will be able to live with,” Secchi said. “But their heart is in the right place in that they are trying to reduce through their consumption our impact on the environment.”

Secchi is not a vegan or vegetarian herself, but she refuses to support farmers who participate in the feed lot system. She purchases her meat from local shops and Midwest farmers. She currently has half a pig in her freezer that she received from a small farmer in Minnesota. Grass-fed, locally-sourced meat consumption is not as harmful to the environment, Secchi said.

Thoma’s Meat Market in Iowa City is a local, independent shop that sources all its meat from Iowa with the exception of their chicken, which comes from Illinois. Manager Shawn Janes works full-time at the market and believes the shop offers the Iowa City area meat of higher quality.

“It kind of just gives you a closer connection to what you’re eating,” Janes said. “You’re not going into large feedlots where everything is filled with antibodies. It’s a higher quality of meat.”

Janes said the local market supports smaller farms that emit less greenhouse gas and hold themselves to higher ethical standards.

“It’s fueling the fields and farms around the area instead of stockpiling a bunch of cattle in one small area,” Janes said.

With environmentalists and vegans raising red flags about mass meat production, Iowa corn fields are no longer pure gold. However, farms from the 1920s may offer a brighter future for Iowa. In his 2006 book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, journalist Michael Pollan raised concerns about Iowa’s focus on corn, and wrote about the impacts the crop has on the mass meat production. He points to Iowa farms in the 1920s, when corn was considered the fourth most common crops. Farmers grew a variety of crops such as apples, oats, potatoes, cherries, wheat, plums, grapes, and pears, Pollan wrote.

Like Pollan, Secchi also believes Iowa farms like Brown’s could find economic, environmental and ethical prosperity by shifting away from corn feed. From her research, Secchi believes resistance to more varied crops has to do with tradition. One of her recent studies looked at farmers’ opinions of conservation and sustainable agriculture.

“I think that farmers are very scared because I think that these kinds of changes could really revolutionize the [agriculture] system,” Secchi said. “The average age for farmers is 50. You’ve lived your life using a certain production model. You’re older. Do you really want major scuttlebutt having to change the way you’ve done things?”

She would like to see more farms grow crops for people, not just livestock. Iowa used to grow onions near Bettendorf and melons in Muscatine, Secchi said.

“We’re not just the place where we grow corn and beans,” Secchi said. “What has happened is a lot of those farmers grow feed corn because they can make a lot more money.”

Iowa could grow a variety of legumes, lentils and other plant-based proteins if the state was not so focused on corn, she said.

“I’m not saying don’t subsidize farming,” Secchi said. “I’m saying subsidize farming differently.”